The Tokugawa Shogunate put the Sado Island Gold Mines under its reign by the Sado Magistrate’s Office and launched mining development on a large scale. To organize the production system, various human resources were gathered such as magistrates with administrative skills, mining experts and workers, as well as merchants and craftworkers for supporting gold production from across Japan to the island.

Sado Island is often referred to as a cultural hub or “epitome of Japan.” People who gathered on Sado Island brought their faiths, various cultures and customs. Through close connection with mining activities, they eventually nurtured a mining culture unique to the island that is seen in festivals, rituals, and performing arts.

Festivals and rituals in particular have supported the miners, both spiritually and in strengthening their bonds, as well as playing an important role in maintaining the gold production organization over a long period of time.

We can also see that mining was deeply connected to people's everyday lives, from the crafts such as pottery that originated from mining, the application of mining techniques as well as stone processing, and to water pumping techniques for rice paddies.

The drainage technology used in the mining tunnels was applied to the development of rice paddies. Furthermore, stonemasons who crafted stone mills for smelting gold and silver created architectural materials, such as stone walls and house foundations. They also produced daily items like mortars, as well as stone pagodas and statute of Jizo (Ksitigarbha).

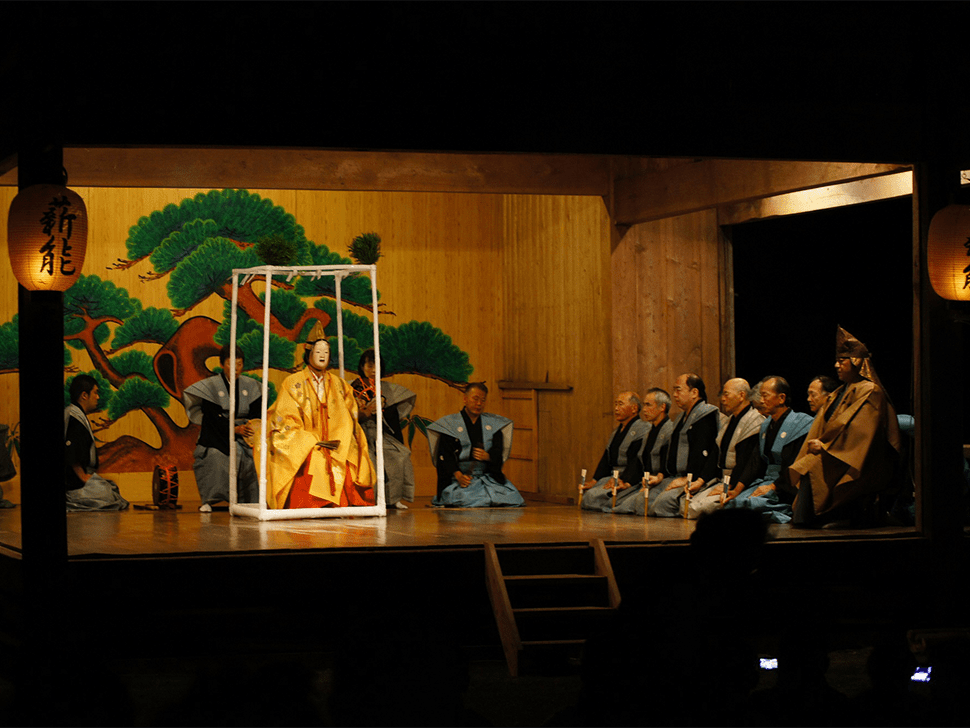

As the gold and silver mines flourished, people from all over Japan came to Sado, bringing their regional cultures with them, In Sado, Noh is still performed in various places across the island. This tradition is said to have begun when Okubo Nagayasu, the first local magistrate, brought a group of Noh performers with him when he arrived on the island.

Yawaragi is a Shinto ritual and performing art that emerged from the mining community. It offers the prayers for the prosperity of mines and for safety of the mining work. The well-known folk song Sado Okesa originated from the Hanya Bushi melody, which was brought to Sado by sailors from Kyushu.

In addition, traditional performing arts such as Onidaiko (or Ondeko) and “Bunya Puppet Play” have deep connections to Sado Mines. Mumyoi ware, a type of pottery made from iron-rich clay from the mines, also has a strong tie to Sado Mines.

Traditional Shinto ritual, Yawaragi

Yawaragi is a Shinto ritual which is said to have been performed near mining sites in the morning of the festival at Oyamazumi-jinja Shrine, where the deity of the mine is enshrined.

The remarkable feature of Yawaragi lies in that the excavation tools are used as costumes and musical instruments. The main performer wears a ceremonial dress (kamishimo) made of straw mat bags, a straw mat tall hat (eboshi), an eye mask, and long whiskers. Sitting in the center, he sings a festive song while waving a stick with streamers (heisoku) at the end. On his both sides are performers with an eye mask, representing miners (kanahori). One of them beats a barrel and the others mimic the action of excavating ore with a chisel and a hammer. Yawaragi has been handed down to this today and is still performed in the festival in front of the altar of Oyamazumi-jinja Shrine.

Yawaragi is said to be performed with two prayers for prosperity of the mine and safety in the tunnels, more specifically:

(1) Softening the hard ore;

(2) Soothing the heart of the mine deity.

Noh Play

More than 30 Noh stages are well preserved on Sado and performances are held from spring to autumn on many of these stages. This proves that Noh culture has been handed down and taken root in life of people on Sado.

Okubo Nagayasu, the first local magistrate dispatched by the Tokugawa Shogunate, came to Sado with a group of Noh actors, laying the foundation for Noh culture on the island. At first, Noh spread to the samurai class in the Magistrate’s Office as educated knowledge. In the middle of the 17th century, Noh play was regularly performed in the Kasuga-jinja Shrine and the Oyamazumi-jinja Shrine. The Honma family and the Endo family, originally from Sado, played a vital role in the popularization of Noh throughout Sado and it gradually spread among merchants and influential figures of towns and villages and was performed at shrines across the island. Although Noh was expensive due to the cost of costumes and masks, it spread across the island based on the wealth gained by mining. Unlike in other areas in Japan, Noh became widely popular even among the ordinary people on Sado, as it provided them with amusement rather than noble art, which allowed it to develop into a unique aspect of Sado culture.

Festival for Uto-jinja Shrine

The annual festival of Uto-jinja Shrine is held on October 19 in the mining town Aikawa. A portable mini shrine and Onidaiko go around the town, celebrating the largest festival on the island. From the Edo Period drawing, we learn that it was a lively festival that people in the mining town took part in. After the portable mini shrine leaves Uto-jinja Shrine, it tours all areas of Aikawa and offers a prayer in front of the gate of the Sado Magistrate’s Office. Meanwhile, in the Onidaiko performance, miners of the gold mines are said to have originally beaten the drum in a manner resembling the act of digging ore. After rituals at the shrine, a portable shrine is carried through the town, while a dancer wearing an old man’s mask dances to the beat of the drum, carrying a bean box in his hand and visiting house to house.

Onidaiko/Ondeko

Onidaiko/Ondeko is a Shinto ritual to ward off evil spirits and pray for family safety and a bountiful harvest. A group of a people acting as demons, some people wearing a lion costume on their heads, whistle players, and drummers visit all the houses in their settlement and dance in front of them. About 120 settlements on the island have their own Onidaiko. Since each of them are handed down orally, it is said that no two Onidaiko are the same. Still, they can be divided into three or five types by their dancing characteristics. It is said that the lineage handed down to Aikawa and other districts began with a festival at the Aikawa Uto-jinja Shrine, and miners were deeply involved it. Onidaiko performance at that time is depicted in a picture scroll from the mid-Edo period (mid-18th century).

Aikawa Ondo (Bon dance* song)

Aikawa Ondo is said to have originated as a Bon dance song, but it refers not only to the song but also to the dance performed to this song. According to a record in the 1640’s, Aikawa Ondo was performed in the vicinity of the Magistrate’s Office. Later, it was also performed in the presence of magistrates. Engineers and laborers living in the mining town participated in the dance as well.

The wooden plates in the latter half of the 18th century depicted people with masks different in status or occupation (someone may look like a samurai or nun) dancing Aikawa Ondo. According to the Buddhist belief, it was traditionally thought that if you wear a mask while dancing, you transform into a dead person, allowing you to communicate with the dead and welcome them. Another reason for wearing a mask was that showing one’s face in front of the Magistrate’s Office was considered rude. Today, people dance with a slanted straw hat instead of a mask to hide their faces. More than 20 years ago, Aikawa Ondo started to be performed not only in the Bon season, but In June every year at Aikawa-Kamimachi town. the “Early Evening Festival” is held on the main street.

*Bon dance: The spirits of the dead are believed to visit their descendants during the bon season lasting four or five days in the middle of August (July in some areas). Bon dance is performed to welcome the dead and send them off.

Mumyoi-yaki ceramic ware

When tunnels were dug, the red clay rich in iron, mumyoi-do, was produced in the Aikawa Gold and Silver Mine. Originally, it was used as a medicine to stop bleeding. In the first half of the 19th century, it was mixed with pot clay and fired at a high temperature, leading to a success in creating mumyoi-yaki ceramic ware, which is very hard and tight yet light. The traditional techniques have been passed down and today a variety of items including teacups and mug cups are produced. In 2024, Sado Mumyoi-yaki was designated as a traditional craft by the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry.

https://www.meti.go.jp/press/2024/10/20241017001/20241017001.html